Having a shipment of almonds rejected by an overseas port for excessive aflatoxin can be expensive, and it’s especially frustrating when pre-export testing appeared to show that the lot in question was fine.

At The Almond Conference last December, a world-renowned authority on testing commodities for mycotoxins explained how rejections can happen — and strategies for avoiding them — during his presentation titled, “Addressing the Aflatoxin Menace Head On.”

“We often hear from handlers that, ‘We tested it here and it passed, but then when we send it over, they say it didn’t pass,’” said Dr. Thomas B. Whitaker. “[In my presentation] I was trying to show the handlers why, and that we can predict the chances of these things happening.”

A professor emeritus at North Carolina State University and retired from the USDA Agricultural Research Service, Whitaker has authored or co-authored more than 150 scientific articles on the subject.

Testing methods leave some uncertainty

No testing protocol is perfect. Some good lots will be rejected by the testing protocol (exporter’s risk) and some bad lots will be accepted by the testing protocol (buyer’s risk). These two risks exist with any testing protocol. Though improvements have been made in how countries reduce these risks when testing for aflatoxin, there is always some uncertainty associated with sampling, sample preparation and quantification steps of the protocol. The largest reason for this is that only a small percentage of almonds in each lot (about one-tenth of a percent by weight) are tested and then used to characterize the whole lot.

To complicate matters, even among almonds with higher levels of aflatoxin (most often associated with insect damage) the percentage of contaminated kernels is extremely small (an estimated 1 kernel per 1,000) and the kernels are not evenly spread throughout the lot. While efforts are made to collect representative samples from throughout the consignment, there can still be significant variability in sampling results, especially when aflatoxin levels are high, Whitaker said.

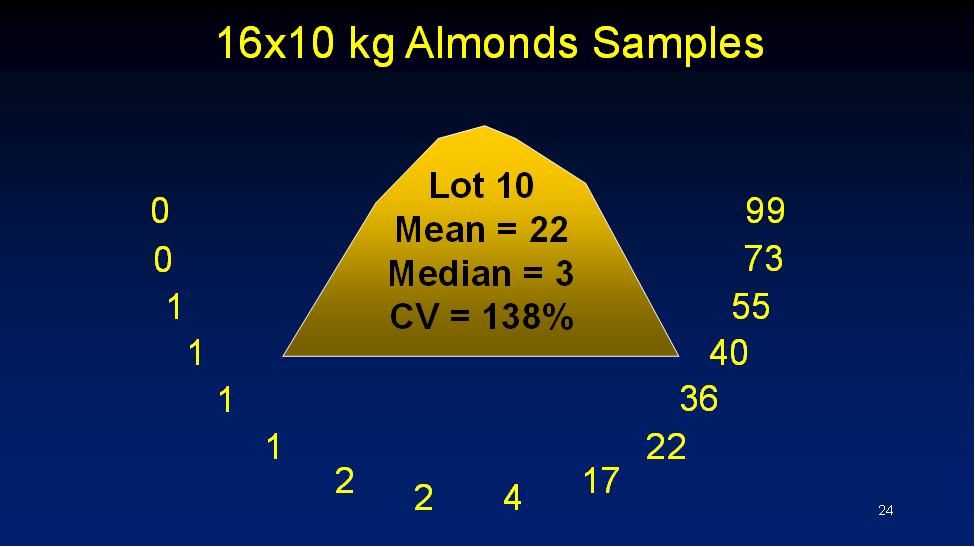

During his presentation, Whitaker gave one example (see Figure 1 below) where samples were taken from a bulk commercial lot of almonds with a relatively high amount of aflatoxin (about 22 parts per billion) and tested 16 separate times (16 10-kilogram samples). Nine of the sample test results were below 10 ppb — which meets the European Union’s limits — while seven other sample test results from the same lot were above 10 ppb, which would lead to rejection.

With extremely low tolerance levels for aflatoxin — as little as 10 parts per billion for shipments headed to the European Union — even a small amount of variability can make the difference between whether a shipment is accepted or rejected by both the almond industry export sampling plan and the European Union sampling plan.

“This shows how a shipment can pass here, but then be rejected over there,” Whitaker said.

Rejections increase in bad years

When aflatoxin levels increase in “bad” years — that is, when environmental conditions make almonds more susceptible to insect damage, such as during droughts — rejected shipments can increase even though the same testing methods are used. That’s because even though the U.S. testing protocol catches many of the highly contaminated lots, a certain percentage gets through. In years with low aflatoxin levels, rejected shipments overseas can drop to less than half a percent. But as aflatoxin levels rise, rejects can spike significantly higher, even though far more shipments are caught before export.

“In a sense, these higher levels of aflatoxin can overwhelm the testing protocol,” Whitaker said. “There is nothing wrong with your testing protocol; what is happening is more aflatoxin-contaminated lots are in the system and more contaminated lots are accepted for export.”

These conditions all lead to greater risks for exporters and importers.

The solution for exporters, Whitaker advises, is to be prepared in bad years and not wait for more shipments to be rejected in the European Union. Rather, if warning signs (such as higher levels of insect damage or poor quality) begin to show up, or climate conditions have predicted a tough year for quality, then the percentage of lots rejected by the almond industry export sampling protocol can be used by handlers to adjust their criteria for passing consignments in the U.S. to reduce lots rejected in the European Union.

A key potential strategy during these years is to test shipments at a lower tolerance; for example, at 5 ppb (parts per billion) instead of the standard 10 ppb. This greatly reduces the chances that shipments will be rejected overseas and gives the handler the option to manage the quality on this side of the ocean through additional processing or to seek alternate markets where tolerances are higher than the European Union. This is precisely what the industry decided to do for last year’s crop, as the ABC Board of Directors approved the change that went into effect in April 2018. And this strategy is paying off: since lowering the accept criteria in the U.S., we have seen a decrease in rejections in the EU.

The strategy for modifying the almond industry export sampling plan is based upon a scientific study conducted by Whitaker and Almond Board staff to show the effect of high levels of aflatoxin contamination in almonds on the percentage of US lots rejected at their destination by the European Union.1

A general discussion about random variability associated with sampling, sample preparation and quantification associated with a mycotoxin testing protocol can be found at this YouTube video.

Success key to maintaining confidence in almonds

“Though aflatoxin is a natural occurrence when growing almonds, and some variability in test results is expected, managing the issue carefully is an important priority for the Almond Board of California,” said Julie Adams, ABC vice president of Global Technical and Regulatory Affairs.

“While countries do accept that there is a certain degree of variability in the crop,” Adams said, “the priority is always going to be compliance with that country’s food safety standards and regulatory requirements. When we are met with conditions such as higher insect damage, it’s a challenge we must manage, because it can potentially undermine an importing country’s confidence in our food safety system.”

Minimizing rejections of shipments helps maintain confidence among importers, customers and government authorities, while also avoiding adverse outcomes for exporters.

“We understand this can be a really frustrating and economically challenging situation,” Adams said. “That’s why it is important for us to not only work closely with our industry here in California, but to also keep the authorities export markets aware of the steps we are taking to manage the situation and minimize the opportunity for rejections.”

Handlers wanting to learn more about aflatoxin can find resources on the Almond Board website or contact Tim Birmingham at tbirmingham@almondboard.com.

Published: January 2019

[1] Whitaker, T., Slate, A., Adams, J., and Birmingham, T. 2010. Number of export lots rejected in the EU due to USA sampling plans and aflatoxin contamination levels among lots tested. World Mycotoxin Journal, 3:157-168.